Scope and objectives of GHEX¶

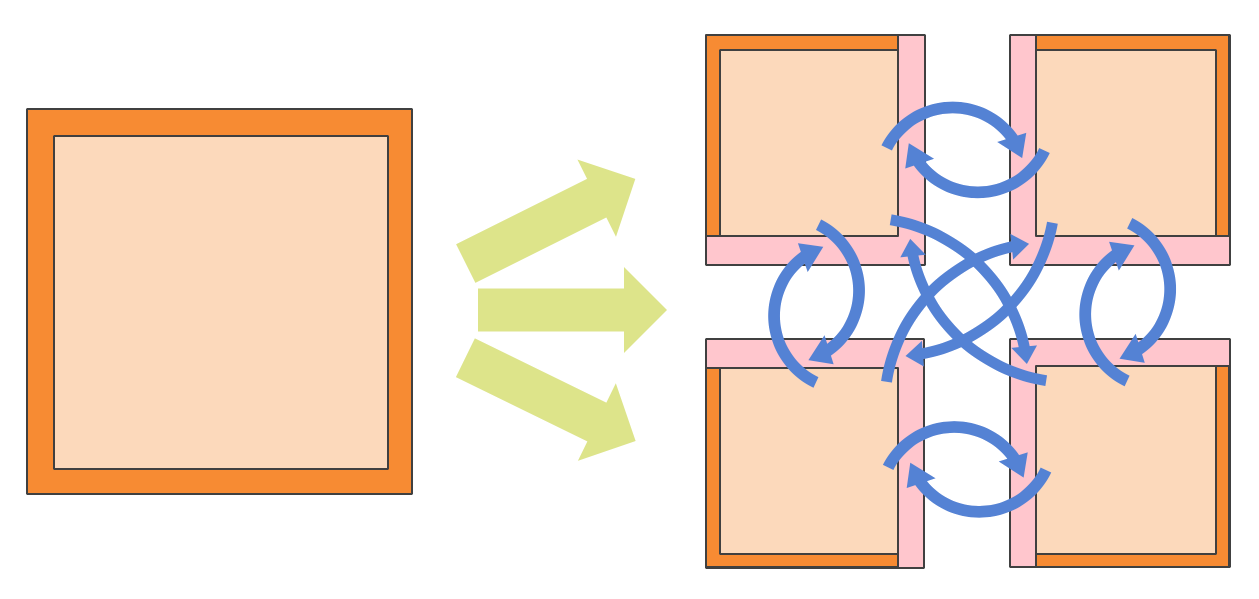

GHEX is a C++ library to perform halo-update operations in mesh/grid applications in modern HPC architectures. Domain decomposition refers to the technique that applications use to distribute the work across different processes when numerically solving differential equations. For instance, see the next figure for a schematic depiction of this idea.

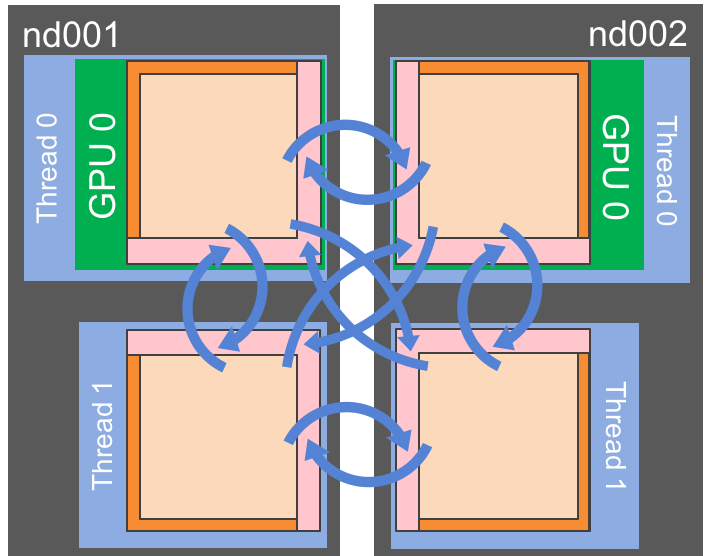

Fig. 1 Example of Domain Decomposition. The physical domain, on the left, is split into 4 different sub-domains. To allow for the computation to progress without having to remotely access every single element that resides on a remote process, the application uses ghost regions, or halos (in pink), that need to be updated whenever the computation requires accesss to that region. The blue arrows show the communication pattern, also referred in the manual as halo-update, or halo-exchange operation.¶

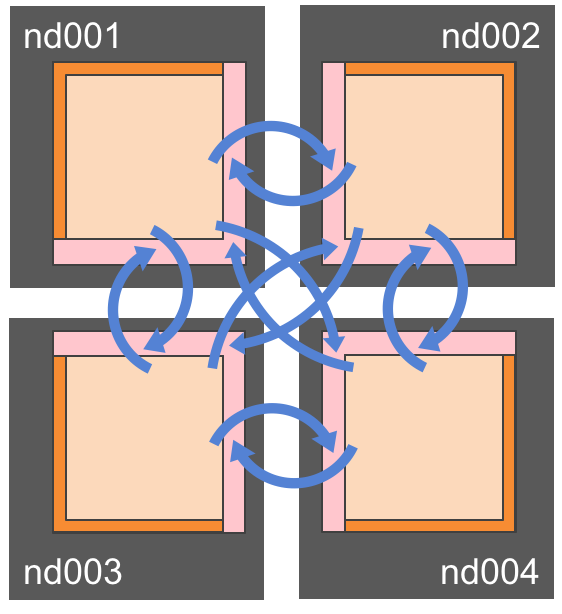

Fig. 2 Traditional distributed memory data distribution: one process (MPI rank) is responsible for one sub-domain of the decomposed domain.¶

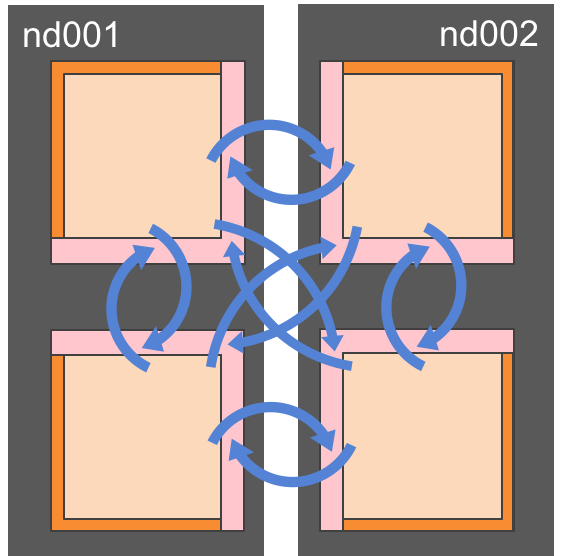

Fig. 3 Each process in a node can manage more than one sub-domain, for instance to achieve load balancing (over-subscription).¶

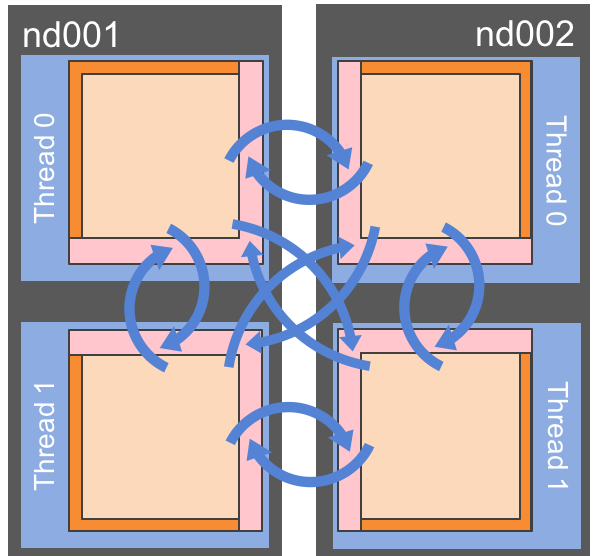

Fig. 4 The over-subscription can be a tool to improve the parallelization in each process by running computations in independent threads.¶

Fig. 5 Using accelerators is certainly one of the most attractive options for running HPC applications on current and near future platforms. The execution can be symmetric, or hybrid.¶

The objective of GHEX is to enable halo-update operations

for traditional domain decomposed distributed memory applications (i.e., one domain per node) either on CPUs or GPUs

for applications applying over-subscription on a node, either for latency hiding or for exploiting multi-threading

for application exploiting hybrid systems (nodes with multiple address spaces and multiple computing devices)

regardless of the specific representation of the grid/mesh (by using adaptors)

on architectures that provide access to transport mechanisms other than MPI (e.g.,

UCXandLibfabric) whose performance may be higher

In order to accomplish all of the above, the interfaces to GHEX requires a non trivial amount of work on the user side. The reward for this work is: portability to multiple architectures, with and without accelerators, with the possibility to exploit native transport mechanisms. Depending on the complexity of the application, a user can easily adapt it to use different number of threads, or different types of threads. GHEX can accommodate these requirements quite flexibly.

Features¶

GHEX employs a number of different communication strategies to improve performance of information exchange. In particular, the following features are available:

off-node access: use of a buffered communication for remote neighbors and reduction of the amount of messages by coalescing data with the same destination into larger chunks

in-node access: taking advantage of direct memory access within a shared memory region when run with multiple threads (native) or when run with multiple processes (through XPMEM)

latency hiding: computation - communication overlap is possible through an explicit future-like API

cache friendliness: structured grids are traversed in a cache-friendly way to avoid cache misses when serializing/deserializing data (for remote connections) and when directly accessing memory (for node-local connections)

avoid serialization: certain types of unstructured meshes can be configured such that serialization on one side of the communication can be avoided

heterogeneity of data: different types of data (with different neighbor regions) may be exchanged in one go

GPU accelerators: carefully tuned serialization kernels which exploit the bandwidth and asynchronous execution

Type of interfaces¶

GHEX has a layered structured. The user can enter at different layers, depending on their needs.

The highest level is the halo exchange level, where the user instructs GHEX to take a mesh or

grid representation and produce a communication pattern to then perform the halo update

operations.

In order to enable all the previously mentioned features, like oversubscription, alternate transport layers and hybrid computations, the steps to create a pattern and use it to communicate can seem overly complicated. While we are working on shortening the number of steps to take for simple cases, more complex cases seem to require these complications, and hence they cannot be avoided. As we expect applications to become more and more complex in the future, we think the use cases in which the interfaces provided by GHEX will increase and overshadow the traditional distributed memory applications simply based on MPI.

The main concepts needed by GHEX are:

Context : Provides information to the application about network connectivity. A computing node, that can be identified with a process (or an MPI rank, for instance) needs some information about how it is connected to other processes.

Communicator: Represents an end-point of a communication, and is obtained from the context (this are hidden when using the halo-exchange facilities, this is why the description is placed at the end of the chapter).

Communication Pattern: Provides application-specific neighbor connectivity information (encodes exposed halos for sending and receiving, for instance)

Communication Object: Is responsible for executing communications by tying together Communication Pattern, Communicator, and user-data.

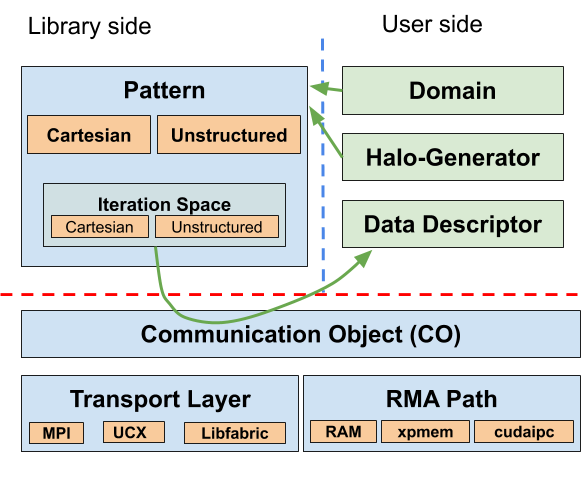

The following figure depicts the different components and their interactions:

Fig. 6 GHEX Software architecture. On the right the main libraru components to set up the halo update operations, on the bottom the main components to perform the exchanges, on the right the user input required by GHEX.¶

Domains, halo-generators, and data descriptors are provided by the users, while the light-blue boxes are provided by the GHEX library. Some user provided components are also provided by GHEX if their implementation is found on common infrastructures, for instance, in Cartesian grids, or ParMeTis partitioned graphs, or the Atlas library for meshing and domain decomposition by ECMWF.

All these components live in contexts, that are the only platform specific interfaces of GHEX. This allows for the GHEX codes to be portable across architectures in the sense that the sections of the code impacted by the different characteristics of the architectures are confined in limited places that can be easily controlled.

Context¶

The context manages the underlying transport layer. Among its tasks are initialization, connectivity setup, communication end-point management, network topology exploration. It is the first GHEX entity that is created and the last that is being destroyed (enclosed only by MPI initialization and finalization). Contexts maintain state information that the communicators need in order to function. In other words, communicators (presented below) cannot outlive the contexts from where they were obtained. Initialization of contexts is platform specific, since different transport layers require different information in the setup phase. Contexts assumes that MPI is already initialized at the time of initialization. An MPI communicator is passed to it as first argument, while subsequent arguments may be required for non-MPI transport layers, such as UCX and Libfabric.

GHEX assumes the availability of an MPI library implementation on the platform.

While this is not strictly needed conceptually, the vast majority of HPC applications rely on MPI

(for instance by using PGAS languages or runtime-systems such as HPX) and, thus, we can take

advantage of the infrastructure provided through MPI for our implementation. This simplifies creation

of contexts and collection of information about which processes participate in the computation.

Therefore, the context requires an MPI Communicator as runtime argument, in addition to other

possible transport specific arguments. The passed MPI Communicator will be cloned by the context.

For this reason the context should be destroyed before the call to MPI_Finalize.

Contexts are constructed for a specific transport layer. The available transport layers are: MPI, UCX, and Libfabric. The transport layer is represented by a tag passed as template argument to the context type.

In order to guarantee uniform initialization of the contexts, which are highly platform dependent,

the user should not call the constructor of the context directly, but instead the use should use a

factory, which returns a std::unique_ptr to context object instantiated with the proper

transport layer. The syntax looks like this:

#ifdef USE_UCX

using transport = gridtools::ghex::tl::ucx_tag;

#else

using transport = gridtools::ghex::tl::mpi_tag;

#endif

auto context_ptr = gridtools::ghex::tl::context_factory<transport>::create(MPI_COMM_WORLD, other_args);

In the above example the use of #ifdef is an example of how code can be made portable by minimal

use of macros, and a recompilation.

From the context, additional information can be obtained, such as the

context<TransportTag>::rank(), which is the unique ID of the process in the parallel execution,

and ranges from 0 to context<TransportTag>::size() - 1.

A context object is instantiated by the processes, but different processes in a computation should instantiate contexts in the same order. The contexts instantiated, one per process, form a kind of distributed context, since they are connected to one another. Suppose we have the following code, executed by a certain number P of processes:

auto context_ptrA = gridtools::ghex::tl::context_factory<transport>::create(MPI_COMM_WORLD);

auto context_ptrB = gridtools::ghex::tl::context_factory<transport>::create(MPI_COMM_WORLD);

The instances of context_ptrA in the P processes form a distributed context, those instances

are connected to one another. The communicators (see below) obtained from it can communicate to one

another directly. The same for the communicators obtained from context_ptrB. Communicators from

context_ptrA cannot communicate directly to communicators from context_ptrB.

Note

Thread safety: A context shall be created in a (process-)serial part of the code. Usage of a context is thread-safe.

Communication Pattern¶

In order to perform halo-update operations, the user needs to provide information about the domain, the domain decomposition, the sizes of the halos and the access to the data. One of the most important aspects of GHEX is the choice of not imposing a domain decomposition strategy, that would possibly result in sub-optimal solutions or not match the developer thinking process. Instead, the user is providing descriptions of the above mentioned concepts as adaptors to their implementation. After all, domain decomposed applications all have to refer to similar information, even though the encoding of this information differs in all sorts of details in different applications. The user of GHEX needs to provide standard functions that GHEX will call to gather/access the necessary information, and these functions form a thin layer that interfaces the specific domain decomposition implementation and GHEX. We are providing some components directly, in order to facilitate the interfacing in the most common cases and showcase the approach.

The communication pattern itself encodes the neighbor information with respect to a domain decomposition and halo shapes. The way GHEX digests user input is through adaptor classes. Since structured and unstructured grids are rather different, we have decided to specialize all concepts and classes for either case. Let us first look at the structured grids.

For a given application, the following concepts need to be implemented:

domain descriptor: a class which describes a domain which provide (at least) the following interface

// this class must be (cheaply) copy constructible.

public: // member types

using domain_id_type = ...; // a globally unique id type which can be compared

using dimension = ...; // A integral constant

using coordinate_type = ...; // An array-like type

public: // member functions

domain_id_type domain_id() const; // returns the id

const coordinate_type& first() const; // returns the coordinate to the first (physical)

// point in global coordinates

const coordinate_type& last() const; // returns the coordinate to the last (physical)

// point in global coordinates

Note that the constructors, or any additional functionality, are not shown here, since they are not needed by GHEX. The user of GHEX construct those and give the objects with those prescribed characteristics to GHEX.

The domain_id_type needs to be comparable, and at least operators < and == should be provided.

domain region

public: // member functions

const coordinate_type& first() const;

const coordinate_type& last() const;

halo region

public: // member functions

const domain_region& local() const;

const domain_region& global() const;

halo generator: a class which generates a halo given a domain descriptor, with the following interface

public: // member functions

std::vector<halo_region> operator()(const domain_descriptor& dom) const;

halo_region intersect(const domain_type& d,

const coordinate_type& first_a_local, const coordinate_type& last_a_local,

const coordinate_type& first_a_global, const coordinate_type& last_a_global,

const coordinate_type& first_b_global, const coordinate_type& last_b_global) const;

Creation of a pattern container:

template<typename GridType, typename Transport, typename HaloGenerator, typename DomainRange>

auto make_pattern(context<Transport>& context, HaloGenerator&& hgen, DomainRange&& d_range);

with GridType equal to structured::grid.

In the case of unstructured grids:

Communication Object¶

field descriptor:

public: // member types

using value_type = ...; // fields value type

using arch_type = ...; // fields location (cpu or gpu)

using dimension = ...; // integral constant with the number of dimensions

// including possible additional dimensions due to

// multiples components

using layout_map = ...; // memory layout (gridtools::layout_map<...>)

using coordinate_type = ...; // an array-like type with basic arithmetic operations

public: // queries

typename arch_traits<arch_type>::device_id_type device_id() const;

domain_id_type domain_id() const;

const coordinate_type& extents() const;

const coordinate_type& offsets() const;

const auto& byte_strides() const;

value_type* data() const;

int num_components() const;

bool is_vector_field() const;

public: // member functions

template<typename IndexContainer>

void pack(value_type* buffer, const IndexContainer& c, void* arg);

template<typename IndexContainer>

void unpack(const value_type* buffer, const IndexContainer& c, void* arg);

Communicator¶

A context generates and keeps communicators. A communicator represents the end-point of a communication and is obtained from a context. Communicators coming from different contexts cannot communicate with one another, creating isolation of communications, which is useful for program composition and creating abstractions.

To get a communicator, the user calls

auto comm = context_ptr->get_communicator();

In order to keep the API simple, get_communicator will return a new communicator every time

the function is invoked. The function is thread safe, and each thread of the computation can call it

and obtain a unique communicator object. A thread should call get_communicator only to get the

communicator objects it needs and should never invoke get_communicator to retrieve a

previously generated communicator. The user is responsible for keeping the communicators alive for

the duration needed by the computation. get_communicator must be called once for each

communicator instance needed.

Note

If an application is only concerned with available high-level halo-exchange facilities (implemented in the patterns and communication objects, see below), a communicator is never directly used by the application. The API of the communicator explained below may however be used to implement more complex scenarios where the application does not follow the typical bulk halo exchange strategy.

Once a communicator is obtained, it can be used to send messages to, and receive from, other communicators obtained from the same distributed context, as explained in the previous Section.

Communicators can communicate with one-another by sending messages with tags. There are two types of

message exchanges: future based and call-back based. The destination of a message is a rank,

that identifies a process/context, and a tag is used to match a receive on that rank.

Communicators do not directly communicate to one-another, they rather send a message to a context and by using tag-matching the messages are delivered to the proper communicator requesting a particular tag. Communicators are mostly needed to increase concurrency, since different channels can be multiplexed or demultiplexed, depending on the characteristics of the transport layer.

For instance, when using the MPI transport layer, multiple Isends and Irecvs are issued by

different communicators, and the concurrency is managed by the MPI runtime system that should be

initialized with MPI_THREAD_MULTI option. In UCX we can exploit concurrency differently: each

communicator has its private end-point for sending, while the receives are all channeled through a single

end-point on the process. This choice was dictated by benchmarks that showed this solution was the

most efficient. The same code runs with MPI and UCX transport layers, despite a different way

of handling concurrency and addressing latency hiding.

Note

While this leaves the tag management to the user, it avoids unnecessary restrictions for the avaialbe tags, which are a scarce resource in some implementations (that is, the tags only allow the use of few bits). Identifying the communicators directly would have required predetermining the number of bits to assign for the local identyfiers and the bits used for rank identification, which can lead to potentially hard to catch bugs. We may revise this decision in the future.

Let’s take a look at the main interfaces to exchange messages using communicators:

template<typename Message>

future<void> send(const Message& msg, rank_type dst, tag_type tag);

template<typename Message>

future<void> recv(Message& msg, rank_type src, tag_type tag);

template <typename Message, typename Neighs>

std::vector<future<void>> send_multi(Message& msg, const Neighs& neighs, tag_type tag);

The first function sends a message to a given rank with a given tag. The message can be any class

with .data() member function returning a pointer to a region of contiguous memory of

.size() elements. Additionally, the message type has to expose a typedef value_type

identifying the type of element that is sent. The function returns a future-like value that can be

checked using .wait() to check that the message has been sent (the future does not guarantee the

message has been delivered). This variant does not take ownership of the message (but refers to

the address of the memory only) and the user is responsible to keep the message alive until the

communication has finished.

Similarly, the second function receives into a message, with the same requirements as before, and

returns a future that, when .wait() returns guarantee the message has been received.

The third function conveniently allows to send the same message to multiple neighbors, and returns a vector of futures to wait on.

The communicator also has a secondary API where a user-defined callback may be registered, which is called upon completion of the communication:

template<typename Message, typename CallBack>

request_cb send(Message&& msg, rank_type dst, tag_type tag, CallBack&& callback);

template<typename Message, typename CallBack>

request_cb recv(Message&& msg, rank_type src, tag_type tag, CallBack&& callback);

template <typename Message, typename Neighs, typename CallBack>

std::vector<request_cb> send_multi(Message&& msg, Neighs const &neighs, tag_type tag, const CallBack& callback);

Here, the functions accept callbacks that are called either after the message has been sent (not necessarily delivered) or received, respectively. The requirements on the message type stay the same as before, however, the type of the message will be type erased in the process and the callback must expose the following signature:

void operator()(message_type msg, rank_type rank, tag_type tag);

where message_type is a class defined by GHEX fulfilling the above message contract with

value_type being unsigned char. Thus, the msg object provides access to the same data as the

message passed to GHEX originally, reinterpreted as raw memory.

GHEX makes a distinction based on the type of the message which is passed to the functions above:

if the message is moved in (has r-value reference type), the communicator takes ownership of the message and keeps the message alive internally. The user is free to delete or re-use the (moved) message directly after calling the function.

if the message is passed by l-value reference, the same requirements apply as above: the communicator does not take ownership of the message and the user is responsible to keep the message alive until the communication has finished.

Note

When the callback is invoked, the message ownership is again passed to the user, i.e. the user is

free to delete or re-use the message inside the callback body. However, when the user re-submits

a further callback based communication through the above API from with the callback (recursive

call) , the message must passed by r-value reference (through std::move).

Note

Since GHEX relies on move semantics of the message internally, the message type must not re-allocate memory during move construction and the memory address of the data must remain constant during the communication.

The send/recv functions accepting call-backs, also return request values that can be used to check if an operation succeeded. However, these requests may not be used like futures: they cannot be waited upon. Instead, to progress the communication and ensure the completion, the communicator has to be progressed explicitly:

progress_status progress();

This function progresses the transport layer and returns a status object. The status object can be queried for the number of progressed send and receive callbacks.

A third API is provided for messages wrapped in a shared_ptr:

template<typename Message, typename CallBack>

request_cb send(std::shared_ptr<Message> shared_msg_ptr, rank_type dst, tag_type tag, CallBack&& callback);

template<typename Message, typename CallBack>

request_cb recv(std::shared_ptr<Message> shared_msg_ptr, rank_type src, tag_type tag, CallBack&& callback);

Here, the ownership is obviously shared between the user and GHEX.

Note

Thread safety: A communicator is thread-compatible, i.e. it is created per thread. One must not use the same communicator from more than one thread.